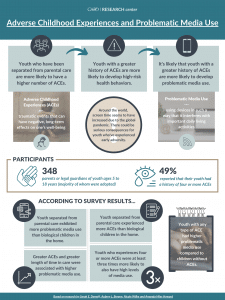

New findings from the CAFO Center on Applied Research indicate that children who have experienced Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) may be more likely to overuse screens.

While ACEs and other history of what’s often referred to broadly as “trauma” are very serious matters, however, they are not destiny. Rather, the special challenges associated with ACEs indicate the need for special attention, effort and perseverance on the part of parents and others who care. Substantive healing and remarkable growth is possible, but often takes much more time and effort than for other children — perhaps much more than we imagined at the start. This new research indicates that this kind of parental attention and perseverance may be particularly important when it comes to regulating and guiding children’s use of technology.

Nearly all of us have seen our screen time go up over recent years. Smartphones, once held by only a third of the American population a decade ago, are now in 97% of adult hands. We absorb our news by scanning a screen, plan events and activities by tapping a screen, and share snapshots of our lives with others via a screen. In fact, you are almost certainly engaging with a screen as you read this article!

Over the past 18 months of living through a global pandemic, screen time has increased even further for much of the world’s population. For many, school, work, and social interaction — once almost exclusively face-to-face endeavors — were largely relegated to the digital world.

The same is true for the young adults and children in our lives. Whether by choice or necessity, their screen time and media use have increased exponentially as well. While there are many research articles that explore the impact of this additional media use on developing brains, there is far less research on its impact on developing brains that have been impacted by significant trauma.

For many of us involved in child welfare efforts, the children we love have experienced situations and circumstances that we decidedly do not love. Apart from the long, hard work of healing, this history can make them more prone to respond to even small challenges with fight, flight, or freeze. In our daily interactions, these responses may be relatively easy to detect. But how do they manifest themselves in children’s media use and screen time? When does media use become problematic?

Problematic media use is using devices in a way that interferes with important daily living activities. In a recent study co-published by the CAFO Center on Research for Vulnerable Children and Families, survey respondents shared about the media use of the biological, adopted, and foster children in their care. By examining the caregivers’ reports of their children’s Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and problematic media use, researchers were able to explore any connections that may exist between the two.

What they found was notable, but not surprising. Of the 348 caregivers, 49% reported that their children had a history of four or more ACEs. These children were at least three times more likely than children with fewer or no ACEs to have high levels of media use. Caregivers also reported more symptoms of problematic media use than those reported for biological children. Overall, this preliminary research seems to indicate that children who have experienced more ACEs are more likely to use media at what is considered problematic levels.

What causes this correlation between childhood adversity and a tendency to overuse media? That remains an open question. Is it that insecurity or other struggles drive a person to find solace in the easily-controlled world of screens? Might difficulty forming bonds with parents or friends make online interactions or the distraction of entertainment more attractive? Are struggles with impulse control — which tend to be correlated with high ACE scores — at the root of the problem? Or might parents who are worn thin by the constant effort required to help a wounded child to grow and heal be more prone to allow their son or daughter to spend long hours on screens since screen time seems to keep things calm, at least in the short run? Perhaps the answer includes all of the above.

Even as researchers continue to explore important questions, however, these findings need not be a cause for discouragement or despair. Rather, they are a call to an awareness that leads to intentional action. If children who’ve experienced especially hard things may be especially prone to overuse of screens, those who love them must be especially intentional to set and enforce clear boundaries for both the time and content of screen use.

The truth is, we’d be wise to do this for ourselves as well. (For three simple steps for doing this, see the article “Taming Technology” by Jedd Medefind. For a great book on the subject, see The Tech Wise Family by Andy Crouch.)

Together, we are all learning to care for the children we love. And as we know better, we can do better. Understanding these risk factors can help us be vigilant and discerning in the way we guide our children to steward the gift of media. And perhaps it will help us do the same ourselves.

To read the full research paper, see: Adverse Childhood Experiences and Problematic Media Use: Perceptions of Caregivers of High-Risk Youth.

If you would like to know more about the topic of vulnerable children and technology, take a look at the CAFO Research Center’s resources on Vulnerable Children in a Digital Age.

If you would like to learn more about the CAFO Research Center, you can visit them online at www.cafo.org/research-center.